A Day After Christmas Tale

a good king, a poor peasant and miraculous snow melt

If you liked reading this, feel free to click the ❤️ button on this post so more people can discover it on Substack 🙏

Long ago, so long ago that we remember it as a dark age, there lived a young boy whose father was a Christian and whose mother was a pagan. They were a noble family in the land of Bohemia. Bohemia takes its name from its Celtic ancestors, the Boii, but that was in ancient times; they had been supplanted many centuries before by the Slavic Czechs. Bohemia was a robust land full of great mountains and thick forests filling deep and dark valleys cut by mighty roaring rivers. The youth’s name was Wenceslas.

His family was an old and noble one. Saints Cyril and Methodius introduced Christianity into Bohemia from Moravia, and Wenceslas’ grandparents converted joyfully. His grandfather was a Prince in Bohemia, and he and his wife, Ludmilla, were loved and respected throughout the land.

But Wenceslas’ life was not filled with the ease and comfort you might imagine the son of a Duke to have. Death is the great equalizer; all must face it, from the greatest to the least. When Wenceslas was just thirteen, his father, the Duke of Bohemia, died in battle.

Ludmilla, his grandmother, insisted he leave his mother and come live with them. Ludmilla loved her grandson dearly. When Wenceslas was born, she planted a small seedling tree in his honor and watered it with his bath water each day. The tree grew fine and tall, just as Wenceslas did. His grandparents’ greatest wish was to instruct their grandson in the faith they had so joyfully embraced.

The times, however, were turbulent and filled with rivalries and tensions. Old ways were drifting away as new ones came in. The old religion and beliefs struggled with new ideas and beliefs. Kingdoms shifted, and alliances changed.

Wenceslas’s mother remained a staunch pagan and ruler of Bohemia after her husband’s death. Her son was not of age yet and, therefore, unable to be the ruler. I’m sad to report that in the way that daughters-in-law and mothers-in-law often do, Drahomira, for that was his mother’s name, and Ludmilla did not get along at all. It was not just personality differences that put them at odds, but more frighteningly, it was a vast wedge of religious differences that cut deep.

I am horrified to tell you that the undue influence of Drahomira’s courtiers and councilors influenced her to do something dreadfully wicked. She gave the orders to have Ludmilla strangled to death. This is shocking indeed, but alas, power, politics, and religion are often a deadly combination.

Wenceslas, now living again under his mother's authority, retained his Christian beliefs in secret. However, things were soon to take another turn. Politics, being what they are, saw the winds of power shift a little, and the authorities banished Drahomira for the murder of Ludmilla. This, of course, would not console Wenceslas; it could not make up for the loss of his beloved grandmother and now resulted in the exile of his mother, too.

Drahomira's banishment was providentially timed however, as Wenceslas had just turned eighteen and could now take his rightful position as Duke of Bohemia. What an excellent ruler Wenceslas would be. In a gesture of true kindness and honor, he brought his mother back from exile and forgave her.

From then on, this extraordinary young Duke continued to distinguish himself through acts of generosity and charity. He was dedicated to giving shelter to the homeless and buying the freedom of slaves—especially the freedom of slave children.

It often seems that goodness in this fallen world is despised, and the good die young. So it was that Wenceslas’ younger brother Boleslav rebuked him for mingling with the poor, and he grew jealous of Wenceslas, who by now had a son who would succeed him as the next Duke of Bohemia, leaving no chance of rulership and power for Boleslav.

One day, Boleslav, a wolf in sheep's clothing, to be sure, invited his brother to a feast at the church. But when he arrived, Wenceslas found members of the nobility loyal to Boleslav waiting for him. They stabbed and beat him ruthlessly, with his brother delivering the final blow. So passed Good Duke Wenceslas on September 28th, 929 AD, only 25 years old.

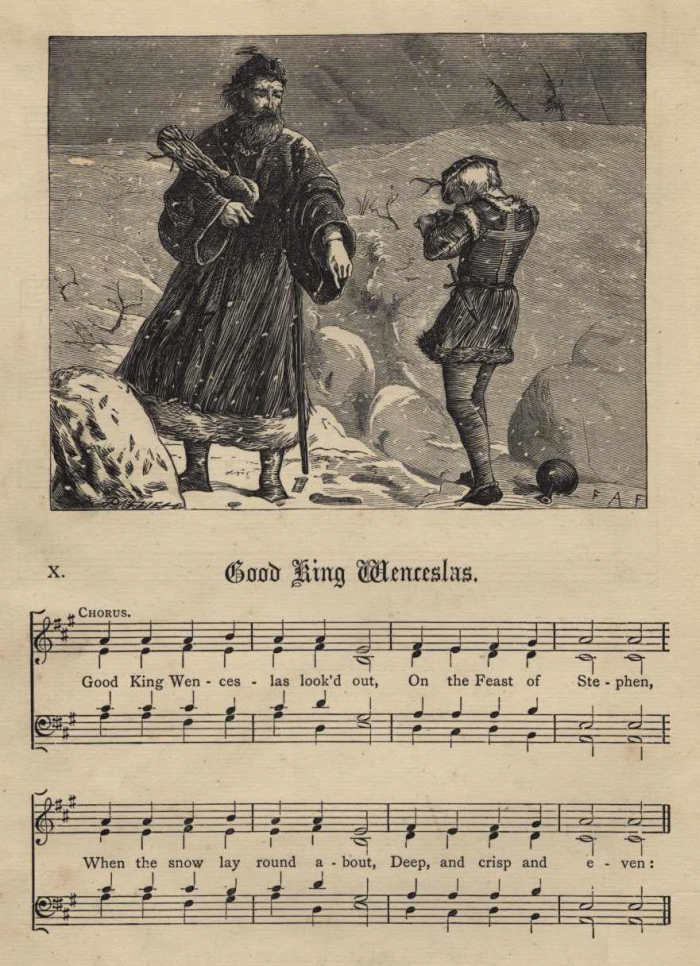

Wenceslas and his generosity have not been forgotten, though. We still know of him today in a Christmas carol, which tells a story about him that takes place on the day after Christmas, the Feast of St. Stephen.

Good King Wenceslas looked out,

on the Feast of Stephen,

When the snow lay round about,

deep and crisp and even;

Brightly shone the moon that night,

tho’ the frost was cruel,

When a poor man came in sight,

gath’ring winter fuel.

“Hither, page, and stand by me,

if thou know’st it, telling,

Yonder peasant, who is he?

Where and what his dwelling?”

“Sire, he lives a good league hence,

underneath the mountain;

Right against the forest fence,

by Saint Agnes’ fountain.”

“Bring me flesh, and bring me wine,

bring me pine logs hither:

Thou and I will see him dine,

when we bear them thither.”

Page and monarch, forth they went,

forth they went together;

Through the rude wind’s wild lament

and the bitter weather.

“Sire, the night is darker now,

and the wind blows stronger;

Fails my heart, I know not how;

I can go no longer.”

“Mark my footsteps, good my page.

Tread thou in them boldly

Thou shalt find the winter’s rage

freeze thy blood less coldly.”

In his master’s steps he trod,

where the snow lay dinted;

Heat was in the very sod

which the saint had printed.

Therefore, Christian men, be sure,

wealth or rank possessing,

Ye who now will bless the poor,

shall yourselves find blessing.

St. Stephen’s Day is an apt day for a story of Wenceslas to be told. For like Wenceslas, Stephen whose concerns lay with the poor, the widows and the orphans also suffered a terrible death at the hands of those surrounding him. The times Stephen lived in, like the times Wenceslas lived in, were also turbulent and filled with rivalries and tensions. Old ways were drifting away as new ones came in. The old religion and beliefs struggled with new ideas and beliefs. Stephen forgave his attackers just as nearly nine-hundred years later Wenceslas would forgive his mother.

The old tales and songs should not be forgotten. In their simplicity and gentleness they remind us of how we should live.

I hope that Good King Wenceslas is somewhere on one of your Christmas playlists. The next time you hear it give a thought to a brave and good young man who cared deeply about the poor and needy and was able to forgive even in the most devastating circumstances.

The comments section is a safe and welcoming space to share your insights and experiences.

Comments and conversation are always appreciated and enjoyed, so feel free to let your voice be heard. I read them all and try to respond to each one.

Thank you for reading Hedge Mystic and participating in this vibrant and growing community of creative, spiritual humans. You are always welcome here, appreciated, and loved.

Hedge Mystic is a reader-supported publication based on a value-for-value premise. If you find value in Hedge Mystic, support my work and consider becoming a free or paid subscriber. Your involvement and financial support are deeply appreciated. Thank you.

What a lovely story, in its way. I was not familiar with it, except for the carol. If only Christians could remember what Christ said, we would see a very different country where I live.

Loved this story, Jan, and passed it on to a few. Thanks so much.